Shtesë » English

Mhill Marku: Father Anton Harapi (1888-1946)

E shtune, 17.10.2015, 07:28 PM

TWENTIETH

ANNIVERSARY OF HIS MARTYRDOM

TWENTIETH

ANNIVERSARY OF HIS MARTYRDOM

FATHER ANTON HARAPI

(1888-1946)

By Profesor Mhill Marku

We cannot speak of any facet of Albanian history where the Albanian Catholic clergy did not play a significant role. Among them, the Franciscans, without any shadow of doubt, were loved and respected by all the Albanians, no matter what creed they professed. A Muslim lawyer, Muzafer Pipa, with full knowledge of the consequences, took upon himself the grave responsilbility of expressing his indignation and that of the Albanians in general at the Red Tribunal of Shkoder when the Franciscan Fathers were being judged and condemned to death on Moscow’s orders in 1946. He was barbarously beaten to death.

Among the Franciscans condemned to shot was Father Anton Harapi, a man who had dedicated his whole life to the spiritual needs of the people, the education of youth and the Fatherland. Father Anton Harapi was born in Shiroke on 5 January 1888. He received his elementary and secondary education at the Franciscan school in Shkoder and studied theology in Tyrol, Austria.

In 1910 we find Father Harapi a teacher in the schools where he had been a student a few years before. But soon Shkoder becomes front page news all over the world with its heroic resistance to the six month siege by the Montenegrins (October 1912- April 1913), On that occasion the Franciscan Fathers gained the love, admiration and respect of the population of Shkoder by feeding the hungry, caring for the sick and wounded and burying the dead without any distinction of religious affiliation or social position.

In the spring of 1916, Dukagjin was afflicted by cholera and people were dying by the hundreds without knowing what had hit them. Father Harapi rushed to Theth and began to visit the families afflicted by the dreadful disease, burying the dead and explaining to the mountaineers how to fight it. He made eight to ten hour trips on foot to visit the families afflicted by cholera. Whole villages had closed themselves in their houses, terrorized, keeping their dead inside waiting for their inevitable destiny.

My grandmother told me: “People would fall down on the streets, in the fields, in the homes remain there and nobody dared to help them, because of the fear of catching the disease. We are shut in with your grandfather dead on the floor covered by a blanket, when one day we heard a voice outside, ‘Is anybody in this house?”

I answered back, “Don’t come in, we are all dying. At once the door that had remained ajar was opened and Father Harapi entered shouting, ‘Open the windows, let the sun and the rain come in! Stand up if you can!’ We stood up, my grandmother said, and to our own surprise we were almost starved, but we did not have cholera or anything else. Father Harapi helped us dig a grave in the orchard and told us to use a lot of hot water and burn grandfather’s clothes.”

This had happened to many families in the mountain villages and all would have died were it not for the courageous and humanitarian work of the humble follower of Saint Francis.

In 1918, we find Father Harapi in Grude caring for the souls and life of the mountaineers. Father Harapi has left us a document of this period which is the best description of the life thought of the Northern Mountaineers of Albania. Here in this book, “Andrra e Pretashit” (Pretashi’s Dream), (published posthumously by one of Harapi’s most remarkable students, Father Danjel Gjecaj), the real figure of the Albanian Franciscan priest, intelligent, dedicated to religion and Fatherland, philosopher, deeply involved in the national, local and individual problems of the people, comes out. This was the time when the existence of Albania was being challenged by her neighbors and the mountaineers as they had done for centuries, rose up to arms to protect their God given rights. Father Harapi was right there with them sharing difficulties and helping them in anyway he could.

In June 1924, we find Father Harapi, and many other Franciscans on the side of Fan S. Noli’s democratic government.

“These were times that we thought the Albanians had turned their backs to the Orient were looking westward towards progress and democracy,” Father Harapi would say later.

But Harapi’s mission as a priest, educator, lecturer, writer, orator of great power went on undiminished. His primary aim was the brotherhood among all the Albanians and the education of the young generations of Albanians. Those who had a good fortune of having him as a teacher, those who heard his sermons from the pulpit, those who heard him speak in the square of the cities of Albania know that his aims were to elevate the Albanians, to spur them to greater deeds and wider avenues of progress.

When chaos and complete anarchy had taken over in Albania, when the perennial enemies of the Albanians, -the slavs-had found Albanians who would kill their brothers and would deliver Albania to an alien ideology, answering the call of the majority of the Albanians together with Lef Nosi, Father Harapi tries to stop the fratricidal war, tries to bring order to chaos, tries to keep together all the Albanians, but unfortunately colossal giants were fighting and the rights of small nation like Albania were not respected and communism triumphed in the land of Skanderbeg.

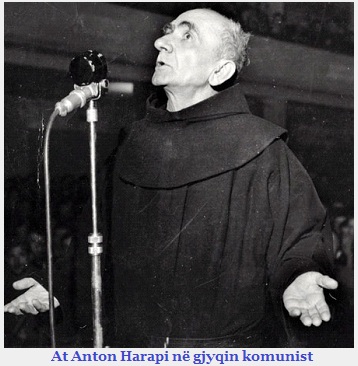

The enemies of Fatherland arrest him with other prominent Albanians. In Tirana, directed by the Slavs, the communists condemn Father Harapi to be shot as a traitor (sic).

His

last words at the Red tribunal were: “If to obey the laws of God and

Fatherland, if to educate the youth and the people and spur them  toward the

high ideals of Truth and Good, if to suffer for the people and with the people

and fight for the Faith and the Fatherland is considered weakness and treason,

then, not only myself but all the Albanian Franciscans deserve the great honor

of being shot. Here, Father Harapi was not speaking to the Red tribunal, but to

the Albanian people and posterity.

toward the

high ideals of Truth and Good, if to suffer for the people and with the people

and fight for the Faith and the Fatherland is considered weakness and treason,

then, not only myself but all the Albanian Franciscans deserve the great honor

of being shot. Here, Father Harapi was not speaking to the Red tribunal, but to

the Albanian people and posterity.

On February 14, 1946, during the night, Father Anton Harapi was taken from the prison and shot. His life and deeds, in the best tradition of the Albanian Franciscans, will remain as an example of unselfish service to his fellow men, and to the Fatherland. The murderers, who buried him in an unmarked grave, as a mockery related later that Father Harapi blessed them and forgave them for shooting him.

We who knew him and loved him remember him today on the Twentieth Anniversary of his death with a prayer and a wish that his ideals of justice and truth return again in our land, so that the Albanians may live and prosper without fear and enjoy, the fruits of freedom in a land of happiness like the one Father Harapi had envisioned.

Gjeke Gjonlekaj: Ky shkrim i mrekullueshëm anglisht i Profesor Mhill Markut ishte botuar në gazetën Dielli me 16 Mars të vitit 1966, me rastin e 20 vjetorit të pushkatimit të At. Anton Harapit.